Visibility Still Matters. Trans Rights in the Low Countries

Thanks to progressive laws and persistent activists, the Netherlands and Belgium lead the way in terms of granting equal rights to transgender citizens in Europe. Such attitudes towards trans welfare and equality did not develop overnight. Even in the Low Countries, the daily struggle against discrimination continues.

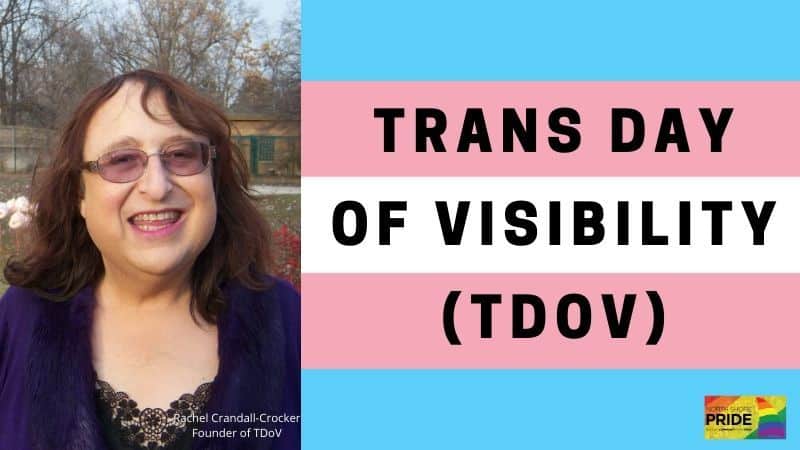

Early in 2009, US-based activist Rachel Crandall founded an event in her home state of Michigan to celebrate the achievements of transgender communities in the fight for equality. Frustrated by the lack of positive representation of trans people in the media, as well as the frequent overlooking of trans issues under the banner of LGBT, Crandall saw Transgender Day of Visibility as a way of ‘expanding the dialogue’ that was developing around trans issues and helping people to ‘focus on the positive aspects of being trans’. Since this inaugural event, Crandall’s home-grown happening has become a global phenomenon and International Transgender Day of Visibility is celebrated annually worldwide.

Rachel Crandall, founder of Transgender Day of Visibility, which is celebrated annually worldwide.

Rachel Crandall, founder of Transgender Day of Visibility, which is celebrated annually worldwide.© North Shore Pride

In terms of visibility for trans issues and the promise of more gender-inclusive policies, there has certainly been much to celebrate in the Low Countries during this past year. In October 2020, for example, Petra De Sutter of the Flemish Green Party (Groen) was announced as Deputy Prime Minister of Belgium. With this matter-of-fact appointment, De Sutter became Belgium’s first transgender minister and, furthermore, the most senior openly transgender politician in the world. As well as having great significance for the increased visibility of trans people in public office, De Sutter has already begun spearheading some of Europe’s most progressive revisions to laws concerning non-binary and intersex people, discussed later in this article.

Petra De Sutter is Belgium’s first transgender minister and the most senior openly transgender politician in the world.

Petra De Sutter is Belgium’s first transgender minister and the most senior openly transgender politician in the world.© Wikipedia

After much lobbying by activists in the Netherlands, the Dutch government also issued a formal apology to transgender citizens in December last year for an earlier law that required those wishing to adjust the gender registration on official documentation to have undergone a sterilization procedure. Following the example set by the Swedish government earlier in 2018, Dutch authorities offered to pay approximately €5,000 in compensation to those who underwent such surgeries, admitting that ‘it is important to acknowledge the suffering of transgender people and to offer recognition, compensation and apologies for it’.

While the Netherlands and Belgium presently lead the way in terms of granting equal rights to transgender citizens in Europe, such no-nonsense attitudes towards trans welfare and equality did not develop overnight. They have, of course, been the project of over a century of activism and innovation.

An umbrella term?

Before delving into the history of transgender visibility and rights in the Low Countries it is important that we first define our terms: to whom are we referring with the term ‘transgender’? Does this label comprise only those individuals who seek to undergo surgeries to align their bodies with their gender identity or does it also include those who conceive of their gender identity as distinct from primary and secondary sex characteristics? And what of those individuals who identify with neither the category male nor female and instead with the perpetual ‘in-betweenness’ of the prefix ‘tra-(ns)’?

Used as an umbrella category for multiple subsets of gender variance, the term 'transgender' has gained mainstream popularity since the mid-1960s

The term ‘transgender’ has been in development for more than a century. Indeed, one of the first studies to shed light on the phenomenon of cross-gender identification was Berlin-based sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld’s study Die Transvestiten (The Transvestites, 1910). As the first major publication to include first-person narratives by trans people, this study crucially gave voice to experiences that had previously been elided from or pathologised within, socio-political narratives. While Hirschfeld had already begun to nuance his terminology in the early 1920s, distinguishing ‘transvestites’, whom he suggested cross-dressed intermittently, from ‘transsexuals’, who desired surgical reassignment to confirm their gender identity, it was not until the mid-1960s when the term ‘transgender’ was coined by psychiatrist John Oliven. Used as an umbrella category for multiple subsets of gender variance, this term has since gained mainstream popularity. Yet, even within trans communities, it has not been universally accepted.

While some people who identify as transsexual reject the label ‘transgender’ on the basis that it implies that their gender identity has not always been constant, others say the umbrella term ‘trans’ is far too broad to have any political purpose. Introducing yet further complexity to the debate are specific sociolinguistic elements. A recent debate in Dutch-speaking countries, for example, has centred around the divisions between those who deploy transgender as a noun (‘a transgender’) and those who have moved toward using the term in its adjectival form (‘a transgender person’), mirroring a more widely employed North American practice.

Although the category ‘transgender’ might be a recent terminological concept, trans people have always existed

The conversation around labels and identities is still very much in flux and its complexities cannot be fully addressed in a single article. For the purposes of this historical overview, however, the terms ‘transgender’ and ‘trans’ are used in their most inclusive forms and refer to individuals outside the notions of ‘male’ and ‘female’, those who traverse gender identities, as well as those who ultimately transition from one category of sex to another.

Although the category ‘transgender’ might be a recent terminological concept, as Alex Bakker states in his latest study Transgender in Nederland: een buitengewone geschiedenis (Transgender in the Netherlands: an extraordinary history, 2018), trans people have always existed. Indeed, we need only glance into Rudolph Dekker and Lotte van de Pol’s Vrouwen in mannenkleren: De geschiedenis van de vrouwelijke travestie (The Tradition of Female Cross-Dressing in Early Modern Europe, 1989) to see colourful examples of gender non-conformists and cross-dressers living in the Low Countries already in the sixteenth century.

Geertje Mak’s Mannelijke vrouwen (Masculine Women, 1997) spotlights further the everyday and extraordinary acts of female gender non-conformity in France, Germany, and the Netherlands during the long nineteenth century. With Bakker’s recent work aside, however, the history of trans experience in the Low Countries in the twentieth century is far less well documented. The following overview describes in broad strokes a rapid period of innovation in trans history and a time during which trans people were able to build on increased social awareness to create supportive subcultural communities, as well as to lobby for law reform and equal rights.

A brief history

As early as the 1920s, gender confirmation surgeries were already taking place in Germany at Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Research. The Netherlands, however, did not lag too far behind in these medical developments. Following the media furore surrounding the transition of American-born Christine Jorgensen in Copenhagen in 1952, countless calls for similar surgeries were heard both in the Netherlands and Belgium. Already in 1959, surgeons at Arnhem’s municipal hospital had performed the first phalloplasty operation on a self-identifying transgender man and, from 1969, confirmation surgeries began to take place more frequently in the Netherlands. As a result of this pioneering work, the first clinic dedicated to transgender issues, the genderpoli, was established at the VUmc in Amsterdam in 1975.

Christine Jorgensen (1926-1989) was a transgender woman who was the first person to become widely known in the United States for having sex reassignment surgery.

Christine Jorgensen (1926-1989) was a transgender woman who was the first person to become widely known in the United States for having sex reassignment surgery.© Wikipedia / Photo by Maurice Seymour, New York

The tendency to view the history of trans pioneers through a lens of medical innovation is not unproblematic. An emphasis on surgery erases the experiences of trans people who did not undergo medical procedures, such as the interwar Belgian mystic Bertha Mrazek/Georges Marasco, for example. Yet, this focus on access to healthcare as a marker of emancipation (and later law reform) highlights the successes of the Netherlands and Belgium in the struggle for equal rights for trans people. Indeed, the concentrated media attention on gender transitions since the 1950s, combined with better access to specialist medical care in the 1970s, enabled trans people to take up greater space in the cultural imagination, making it easier also for activists to occupy a more prominent space in the social sphere.

The Netherlands was one of the first countries in Europe to allow trans people to change their registered gender officially

Against this backdrop, trans people began to lobby not only for increased social awareness but also equal rights as Dutch and Flemish citizens and, in 1985, the Netherlands became one of the first countries in Europe to allow trans people to change their registered gender officially. Four years later, the European Parliament called on the Member States to advance facilities for the support and treatment of trans people. Yet, it was not until twenty years after this that Belgium introduced a similar law in 2007. While the introduction of both laws presents a breakthrough in the history of trans rights, the opportunity to change one’s gender on official documentation was still not a simple process. Rather, it was contingent upon taking hormones, undergoing confirmation surgery and being permanently and irreversibly sterilised.

Maxim Februari, author of The Makeable Man

Maxim Februari, author of The Makeable ManAs author and columnist Maxim Februari suggests in his book De maakbare man (The Makeable Man, 2013), the Netherlands (and, later, arguably Belgium) ‘suffered the disadvantages of being a pioneer in the field of sexuality’. After introducing in 1985 what was, at the time, a progressive bill, trans people in the Netherlands were forced for the next thirty years to undergo intrusive surgeries to be able to change their gender officially. Reflecting the so-called ‘Transgender Tipping Point’, the Netherlands only revised this position in 2014, when it became the first country in the world to allow trans people to change their gender without undergoing mandatory sterilisation procedures. This made gender transition possible for those even without access to medical care. The requirement for gender reassignment surgery and sterilisation was removed from law in Belgium in 2018.

In 2014, the Netherlands became the first country in the world to allow trans people to change their gender without undergoing mandatory sterilisation procedures

It becomes clear, even from this cursory review that access to healthcare and equal rights has not been self-evident for trans people in the Low Countries and the current progressive attitudes have been long fought for and hard-won. But what of the current situation in the Low Countries? How does the experience of trans people in the Netherlands and Belgium differ from surrounding European countries? What obstacles remain in the struggle for equal rights and visibility for trans people?

Current state of play

According to the latest set of ‘Over the Rainbow’ studies from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in the United Kingdom (OECD), the Netherlands and Belgium have recovered from their ‘pioneering disadvantage’ to once again take leading positions in terms of LGBTI inclusivity within Europe once again. As described earlier, both countries have abolished the requirement for medical intervention attached to gender recognition and now allow individuals to change their gender marker based largely on self-determination. In the Netherlands specifically, there has also been a rapid growth in support networks for trans people, with groups such as Transgender Netwerk Nederland, Transgender Info Nederland, Transvisie, TransUnited, and T-Nederland organising regular events and actions. Since 2018 a monthly pop-up clinic has been established in Amsterdam, which serves as a safe space for transgender migrants, refugees, and sex workers. More recently, the first clinic focusing on care for transgender children and adolescents (Radboudumc Centre of Expertise for Sex & Gender) was opened in Nijmegen in 2020.

In the Netherlands and Belgium, there has been a rapid growth in support networks for trans people.

In the Netherlands and Belgium, there has been a rapid growth in support networks for trans people.In Belgium, the OECD reports that significant strides have been made towards protecting transgender and intersex individuals. The number of hospitals and clinics specialising in confirmation surgeries is rising and the support network Genres Pluriels now offers a range of informative material for trans, gender fluid, intersex and non-binary people online, as well as organising in-person gatherings. Furthermore, at the most recent online event chaired by the Global Equity Caucus, Deputy Prime Minister Petra De Sutter announced further changes to the law, signalling that the Belgian government ‘is going to reform the Gender Recognition Law […] to address specifically the situation for non-binary people’ as well as reforming laws concerning ‘medically unnecessary surgeries’ for intersex people. Support for younger trans people and trans children has been growing in Belgium, too, with organisations like T-Jong offering educational tools for families and schools, as well as social networks to support transgender youth in their gender journeys.

The subject of transgender children is a contentious issue, however. The establishment of the Centre of Expertise for Sex & Gender in Nijmegen did not go uncontested, for example, and several ethical questions were raised in relation to the provision of gender-affirming hormone treatment for children and young people. For those opposing medical interventions during childhood, it is of critical importance to be cautious about whether children under the age of sixteen can give informed consent to such treatment and to consider the potential risks of prescribing treatment such as hormone blockers to prepubescent patients.

The Netherlands and Belgium have been paving the way to better care for transgender children since the 1990s

While there is no public or medical consensus on the provision of treatment for transgender children, the Netherlands and Belgium have been paving the way to better care for transgender children since the 1990s, with specialists in Amsterdam and Ghent working together to develop an approach that has since become known as the ‘Dutch Protocol’. As a general framework, the Dutch protocol suggests offering puberty suppression treatments (with parental permission) to children who present with gender dysphoria between the ages of eleven and sixteen. From fifteen to sixteen upwards gender-affirming treatment could be offered to patients, which might include the use of gender-affirming hormones. From the age of eighteen onwards, the protocol suggests that young adults should have access to hormone treatments and gender-affirming surgeries if that is considered appropriate and desirable.

The Dutch Protocol has been taken up slowly in neighbouring European countries. In France, for example, there now exist specialist departments at the Pitié-Salpêtrière and Robert-Debré hospitals that deal with care for transgender children and adolescents. In Germany, too, more clinics are beginning to focus on care for transgender youth and organisations such as Trakine have also been established to advocate specifically for the rights of transgender children to medical care and to offer broader educational and social support for children and their families.

There is still resistance to medical interventions in the care for transgender youth, as well as opposition to the notion of gender self-determination

However, while support networks for transgender children are growing in central Europe, there is still resistance to medical interventions in the care for transgender youth, as well as opposition to the notion of gender self-determination. In December 2020, for example, courts in the United Kingdom ruled against allowing children under the age of sixteen access to hormone blockers without court approval and a recent attempt to allow citizens to determine their gender based on self-identification was defeated in May in the German Bundestag.

In light of these setbacks, the progressive actions taking place in the Netherlands and Belgium are certainly to be welcomed. Yet it would be remiss to imagine there is nothing left to achieve in terms of trans rights and equality in the Low Countries. Only in January 2020, for example, was award-winning YouTuber and beauty vlogger Nikkie de Jager forced to make an emotional coming-out video about her experiences as a transgender woman after being blackmailed about her gender history. De Jager was able to transform this moment into a positive opportunity for activism and awareness-raising, yet her story has highlighted that several important conversations about the issues currently faced by transgender people in the Netherlands and Belgium remain to be had.

In relation to the blackmail faced by De Jager specifically, a gap in the law meant to protect minority subjects from harm means that some crimes against trans people continue to go unpunished in the Netherlands. While the law against hate speech based on sexual orientation has been illegal since 1992, for example, hate crimes (which do not comprise hate speech, it seems) based on gender identity and sexual orientation have not. Furthermore, demonstrators at the recent protest ‘Trans Care Now!’ in Amsterdam signalled that, despite the number of clinics that provide care for transgender people growing in the Netherlands, the medicalisation of ‘trans-ness’ has historically led to gatekeeping actions that ultimately prevent people from accessing the treatment and care that they need.

In Belgium, too, there is still a large spring to make in terms of realising equal protective legislation and access to health care for transgender and non-binary people. At present, the civil registry is not allowed to recognise individuals who do not identify as either female or male, for example, which effectively denies non-binary and intersex people their full civil rights. While De Sutter’s remarks at the Global Equity Caucus point to a positive new direction in this respect, the current situation for non-binary and intersex people in Belgium leaves much to be desired. Furthermore, in neither Belgium nor the Netherlands has the demand for full self-determination of gender identity to be passed into law.

With trans people still facing difficulty in access to medical care, as well as workplace discrimination, blackmail, and physical violence there is much that remains to be done

Indeed, with the term ‘transgender’ still remaining on the national classification of diseases in both the Netherlands and Belgium and with trans people continuing to face difficulty in access to medical care, workplace discrimination, blackmail, and physical violence, it is without doubt that there is still much that remains to be done to achieve equal rights for transgender, gender non-binary and intersex people in the Low Countries. While Pride Month has undoubtedly been a time to celebrate all that has been achieved in the name of transgender rights and visibility, we must now ensure we continue to look forward to the vital transformations that are yet to be made in the name of equality.